Chapter 16

Eugenics, Immigration Restriction and the Birth Control Movements

Engs, Ruth Clifford (2014). Eugenics, Immigration Restriction and the Birth Control Movements. In: Katherine A.S. Sibley (ed.), A Companion to Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover. Wiley Online Library: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Chapter available at Wiley Online Library: Wiley Online Library: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/book/10.1002/9781118834510.

Complete article on IUScholarWorks Repository: https://hdl.handle.net/2022/19003

Abstract

Agitation for eugenics, immigration restriction, and birth control were intertwined during the first decades of the twentieth century along with numerous other health issues.

Campaigns for these causes led to public policies in an effort to improve the physical, mental and social health of the nation. However, these issues were not considered of historical interest until the post-World War II era. Eugenics and the leaders of the eugenics movement were often discredited by late twentieth-century historians as elitists or racists, while early immigration restriction laws and nativism gained renewed interest, and birth control and its early leaders such as Margaret Sanger were both eulogized and demonized. Contested interpretations of all three of these reform movements and their leaders have been found since the 1950s.

Background Information

The importance of the "rights of society" versus "the rights of the individual" goes in and out of fashion. Louis Menand, in the The Metaphysical Club (2001, 441), argues that the "good of society" was more important than the "rights of the individual" in the early twentieth-century compared to contemporary times. Reformers were convinced that controlling reproduction and immigration would reduce disease and welfare costs. Ruth Engs (1991) suggests that these crusades were aspects of the Clean Living Movement of the Progressive Era (1890-1920) and were entwined with various public health campaigns to "clean up America" including Prohibition and the eradication of tuberculosis (Engs 2003, ix-x).

Eugenic efforts and immigration restrictions peaked in the 1920s. However, legal birth control devices and information were not widely available until after 1936 although widespread campaigns for their acceptance were found in the Harding-Coolidge years. Sociologist Henry Pratt Fairchild (1926) brings the themes of this chapter together in his Melting Pot Mistake where he advocates eugenics, birth control, and immigration restriction to improve the human race.

Some terminology and information related to the eugenics, immigration restriction, and birth control movements will likely appear to current attitudes as racist, offensive, unbelievable, or just quaint. Advocates of these reforms were using the correct scientific terms of the time, such as "imbeciles" "unfit," "degenerate," "insane," "defective," "feebleminded," etc. The reader is cautioned, however, to be careful in judging past social and health reformers and their beliefs and activities through the lens of the early twenty-first century, lest we be judged in the future for some of our current attitudes and policies.

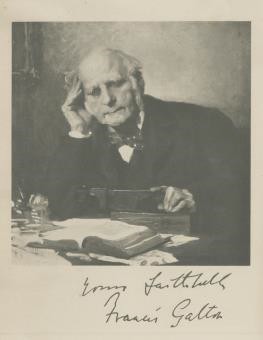

Eugenics, defined by its founder British Naturalist Francis Galton in 1883, and revised in 1904, is "the science which deals with all influences that improve the inborn qualities of the [human] race." (Galton 1904, 1) Its aims were to encourage the "fit" (the intelligent, healthy and productive) to marry and have many children (positive eugenics) and to discourage or prevent the "unfit," including persons judged "insane," "feeble minded," and criminal, for example, from reproducing (negative eugenics) (Saleeby 1914, 19-20). Immigration restriction policies were enacted to prevent "degenerative" Asians and eastern-and southern-European immigrants from degrading the health, heredity, intelligence and traditional values of the Anglo-American culture. Legal birth control would allow women to control their reproduction and sterilization would prevent the unfit from reproducing (Robinson 1922; Laughlin 1922).

The historiography of all these movements, and particularly the eugenics movement, began to proliferate in the 1990s. Due to the numerous monographs and essays on these subjects, and space limitation of this chapter, it is only possible to explore a select number of academics from different fields who have explored and re-interpreted these movements which peaked in the Harding-Coolidge administrations.

This essay will first discuss the origins of the eugenics (also termed race regeneration or race betterment), immigration restriction, and birth control movements drawing largely upon writings of prominent leaders of these campaigns. This will provide insight into accepted beliefs based on the science of the time.

Lamarck, Darwin, and Mendel: the Origins of Eugenics

Eugenics developed out of the intertwining of Darwinism and Lamarckian theory of the inheritance of acquired characteristics. British naturalist Charles Darwin—Galton's cousin—proposed that changes over time in species are the result of natural selection. French naturalist Jean-Baptist Lamarck claimed that characteristics developed from environmental influences were inherited (Darwin 1859; Jordanova 1984).

Lamarck's proposal was the accepted theory of inheritance, until the second decade of the twentieth-century, and was the foundation of "degeneracy theory" in which acquired negative characteristics were thought to be passed to offspring. Individuals for centuries had recognized that traits and behaviors—both good and bad—ran in families. It was believed that racial poisons, such as tobacco, alcohol, and diseases such as tuberculosis and syphilis, could damage the "germ cells"—ovum and sperm. This damage then could be inherited leading to race degeneracy (physical and mental weakening of the human race). (Saleeby 1909, 205).

Gregor Mendel, in 1866, discovered the basic laws of genetics and heredity. But these principles were not rediscovered until 1900 and did not become widely accepted until over a decade later when professionals began to ascribe both positive and negative human traits, such as intelligence or criminality, to Mendelian inheritance exclusively, rather than environmental factors.

Lamarckian inheritance theory, however, remained an undercurrent in some public health and social campaigns to eliminate racial poisons. (Engs 2005, 135; Davenport 1911; Laughlin 1922)

The scientific study of genetics/eugenics began with the formation of the American Breeders Association in 1906. Genetics and eugenics were one and the same until they separated into two disciplines in 1910 and every founding member of the editorial board of the journal, Genetics, was an advocate of eugenics (Ludmerer 1972a, 25). Eugenicists reasoned that if you could breed superior livestock, it should be possible to breed superior humans. However, the early geneticists/eugenicists oversimplified the problem of human genetics (Haller 1963, 3).

The eugenics movement was led by prominent academics and health and social welfare professionals who had deep concerns about the deterioration of the nation. For example, Paul Popenoe, editor of the genetic/eugenic research periodical The Journal of Heredity, and Roswell Johnson, a biology and geology professor at the University of Pittsburgh, discussed in their work Applied Eugenics the "practical means by which society may encourage the reproduction of the superior and discourage that of inferiors." (Popenoe and Johnson, 1922, v). William J. Robinson,

M.D. (1922, 111-112) in Eugenics, Marriage and Birth Control, proclaimed that "society cannot prevent the birth of all the unfit and degenerates, but it certainly has the right to prevent the birth of as many as it can." Stanford University President David Starr Jordan wrote the eugenic booklet The Heredity of Richard Roe (1913). Noted science writer Albert Wiggam helped popularize eugenics through many articles and books. In The Fruit of the Family Tree (1924, 170) he argues that "we should apply science to the problem of marriage" and gave practical eugenic advice to prevent the human race from "slipping backwards."

One of the few women who promoted eugenics was physician Lydia DeVilbiss. In her Birth Control: What is it? (1923) she advocated the sterilization of the unfit. However, she also strongly advocated positive eugenics and asked "when will America be willing to spend as much money in helping to rear the children of the most fit, as they now waste or worse than waste on the offspring of the least fit?" (p. 55)

The most important institution of the eugenics movement was the Eugenic Record Office of Cold Spring Harbor, NY, established in 1910 as "a repository and clearing house for eugenic records of families." Geneticist and the pivotal leader of the eugenics movement, Charles Davenport, was its director and Harry Laughlin, assistant director. This office helped facilitate and coordinate all aspects of the movement in the United States. It also researched the pedigrees of so called "degenerate" families. The Kallikak Family (1912) written by Henry Goddard, director of the Research Laboratory of the Vineland Training school for "feeble-minded boys and girls," was the most noted of the "family history studies" that supposedly showed that criminality, poverty, and mental disabilities were inherited. These studies were used as justification for negative eugenics.

The eugenics movement reached its peak activity and influence in the mid-1920s during the Harding-Coolidge administrations. "Fitter Families" contests at state fairs, derived from the pre- WWI "better babies" contests, began in 1920 to ascertain the health of children and families. The Second International Congress of Eugenics was held at the American Museum of National History in New York City in 1921. The American Eugenics Society (AES) was founded in 1923 with numerous prominent academics, physicians, clergy, and health reformers on its board and advisory council (Huntington 1935, p. iv; Haller 1963, 72, 151-152). "To be against eugenics in the 1920s was to be …against modernity, progress, and science."(Marks1993, 651)

Hierarchy-of-Races and Nativism: Barring "Degenerate" Immigrants

An accepted scientific belief in the early twentieth century was the "hierarchy of races." Sociologist Elazar Barkan (1992, 2-3) notes that "the inferiority of certain races was no more to be contested than the law of gravity to be regarded as immoral." In 1856, Count Arthur de Gobineau in The Inequality of Human Races (1856) had proposed that "Mankind is divided into unlike and unequal parts…arranged, one above the other, according to differences of intellect." (de Gobineau, 196, 181) He divided the human population into three races and placed them on a ladder ranging from the backward, diseased, and unintelligent to highly civilized, healthy and intelligent. People from the African continent were on the bottom, those from Asia were in the middle, and those from Europe were at the top of the ladder.

Later sub-groups of European "races" were classified from desirable to undesirable by naturalist Madison Grant (1916, 122-123 insert), a eugenics, nativist and immigration restriction promoter. Grant defines Northern-European "Nordics" on the top, Eastern-European "Alpines" in the middle, and southern Europeans "Mediterraneans" on the bottom.

De Gobineau claimed that mixing of different races led to degeneration and the decay of a civilization. He argued that a degenerate "people has no longer the same intrinsic value as it had before, because it has no longer the same blood in its veins …in other words, though the nation bears the name given by its founders, the name no longer connotes the same race." (p. 25).

Because this was an accepted belief, many feared that "racially inferior" immigrants intermarrying with "racially fit" "old- stock" Americans would lead to race degeneracy. This concern was an underpinning of nativism—a "pro-American conviction" that the United States should be preserved primarily for white Anglo-Saxon Protestants (Grant 1916, 81-82; Stoddard 1920, 261-262). An important aspect of nativism was Anti-Catholicism which had roots in the conflicts of the Reformation and the American colonists' traditional rural values. After reaching a peak in the formation of The Know Nothing Party of the 1850s and its antipathy toward Irish- Catholic immigrants, nativism went underground during the Civil War (Higham 1955, 5-9; Reimers 1998, 10-12).

In the 1880s, when numerous poor Catholic and Jewish immigrants from southern and eastern- Europe crowded into eastern cities, hostility towards immigrants was revitalized. A flood of Chinese laborers into the west who did not readily assimilate resulted in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1892. The National Quarantine Act of 1893, a public health law, attempted to prevent impoverished and diseased southern and eastern-European immigrants from entering the country (Hall 1906, 84-85; Kraut 1994; Reimers 1998, 11-15). In 1894 the Immigration Restriction League was founded to advocate for stricter regulations of "undesirable" immigrants (Hall 1906, 315-316). Based upon investigations of the federal Dillingham Commission in 1907, sweeping legislation was passed in 1910 that excluded the "feeble minded," "insane," and those with physical and moral defects (Ludmerer 1972a, 25; Martin 2011,137). Nativism fostered the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan in 1916 which embraced eugenics and pushed for immigration restriction, prohibition and public health measures (Evans 1923). (The KKK is discussed further in Chapters 8 and 15).

Nativist sentiments were implicit in the term race suicide –the declining birth rate and decreasing population of "more valuable" middle-class Anglo-Americans. The term, coined by the father of sociology Edward A. Ross (1901, 88) in 1901 was popularized by President Theodore Roosevelt (1905). The fear of racial suicide peaked in the early 1920s and several authors discussed the topic including nativist and anti-immigration leader Lothrop Stoddard who wrote The Rising Tide of Color against White World-Supremacy (1920).

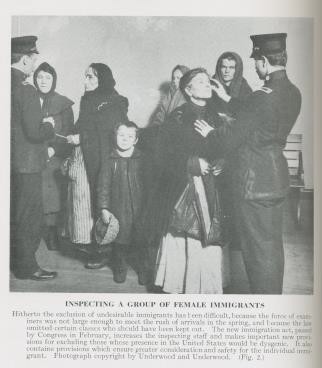

Preventing diseased and unfit immigrants from entering the United States was a major public health concern. Popenoe and Johnson (1922, 303) argued that despite screening for disease, "mental defects are not of an obvious nature and manage to slip through." They expressed concerns that "immigration of recent years appears to be diminishing the eugenic strength of the nation more than it increases it." (p. 317).

The anti-immigration crusade interwoven with eugenics reached its zenith immediately before and after World War I when "middle-class Americans feared a Bolshevik-style political takeover from Russian Jewish immigrants or a Papal takeover from Irish, Italian, and Polish Catholics." (Engs, 2005, 115-117). Madison Grant's Passing of The Great Race (1916) greatly influenced anti-immigration supporters along with the powerful revitalized Ku Klux Klan. Noted Yale economics professor, Irving Fisher (1921, 226) stated that "the core of the problem of immigration is one of race and eugenics." Henry F. Osborn (1923, 9), director of the American Museum of Natural History, suggested, "For America eugenics rests both on birth selection and upon immigrant selection." These opinions were similar to many other nativist and eugenic supporters.

Nativism linked with eugenics peaked with the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act of 1924. In 1920, the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization published Biological Aspects of Immigration which largely consisted of Harry Laughlin's "expert testimony" to the committee. Eugenics supporters, along with the Immigration Restriction League, campaigned for more comprehensive laws. This led to a temporary National Origins Act in 1921 followed by the 1924 act. The bill mandated a quota of foreign born to 2% of the ethnic groups who resided in the country in 1890, which were mostly northern Europeans, and guaranteed that the proportion of new immigrants from southern and eastern-Europe would be small. This national origins exclusion mandate was not revised until the 1965 Celler Act. (Mehler 1988, 2; Ludmerer 1976b, 61)

The Birth Control and Eugenic Sterilization Movements: Preventing Conception

The birth control movement was an aspect of the "woman" or feminist movement of the early twentieth century (DeVilbiss, 1923, 49). Most leaders of the birth control movement were women. The term birth control was coined by Margaret Sanger (1931, 191) in 1914 the founder of the campaign to "cast off the bondage of involuntary parenthood" (Dennett, 1926, 172).

Another early leader was sex education and woman suffrage advocate Mary Ware Dennett. However, Sanger, after clashes with Dennett, in the early 1920s emerged as leader of the movement (Chesler 1992, 233). Many health and social reformers were against the birth control movement including eugenics supporters, such as Popenoe (1926, 145, 148) who thought the crusade was run by "sob sisters" and proposed that the "Birth Control cult should be repudiated by all responsible people."

In the early twentieth-century, educated and well-to-do women were able to obtain contraception. However, in order to make birth control available for poor women, it would be necessary to repeal the 1873 Comstock Law, which prohibited materials on sexuality from being sent through the mail. Contraception information was considered pornography. DeVilbiss remarks that many physicians "under the cloak of professional secrecy" prescribe "therapeutic contraceptives for their patients. But few… have the opportunity or the courage to prescribe for the poor, miserable wretches they so often meet in the free dispensaries and in the wards of charity hospitals." Indeed, to do so would cause them to lose their hospital privileges or risk arrest. (1923, 165-166).

De Vilbiss summarizes the beginnings of the birth control movement. "On October 16, 1916 Margaret Sanger, a trained nurse... opened a clinic in a crowded section of Brooklyn. The story of this clinic, the arrest of Mrs. Sanger and her sister, Ethel Byrne, also a trained nurse, their days in prison, their trials and finally their release will always remain one of the most thrilling chapters in the history of the long struggle for human freedom." (DeVilbiss 1923, 169).

Sanger had previously been indicted for discussing birth control in her newsletter Women Rebel in 1914 and also for a birth control pamphlet Family Limitations. These charges were later dropped.

The birth control movement was ignored by most health and social reformers in the pre-WWI years as Sanger was considered a radical and physicians were sometimes ignorant about the subject. William Robinson was one of the few physicians who openly championed birth control. During the 1920s, agitation for birth control was in full swing and Sanger changed tactics. She forged relationships with the medical profession, courted the middle class and embraced eugenics (Chesler 1992, 216, 277-281; Spiro 2009, 193).

In 1921, Sanger organized the American Birth Control League, an educational and lobbing organization, and the first American Birth Control Conferences in New York City. De Vilbiss, the chair of the conference, instructed physicians on various contraceptive devices. At the last session of the conference, the Catholic diocese, which considered birth control murder, arranged to have the police shut down Sanger's presentation and arrest her. The news media publicized the arrest and over 1500 participants attended the rescheduled presentation (Kennedy1970, 94-99).

Sanger, in 1923, established the Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau, a contraceptive and research clinic which was run as a private practice; the first director was soon let go. Hanna Stone, MD, was hired and carried out detailed research. In 1920, Robert Dickinson, MD, who had decried Sanger's campaigns, was elected president of the American Gynecological Society and began to organize professional interest in birth control. He attempted to run his own birth control clinic but it failed. He created the Maternity Research Council and joined in an uneasy alliance with Sanger to oversee operations of her clinic and collect research data (Chesler 1992, 273-277).

Sanger organized the Sixth International Neo-Malthusian and Birth Control Conference in New York in 1925 and Stone gave preliminary results of birth control methods. At the conference, Johnson proposed a resolution urging larger families by "persons whose progeny gives promise of being a decided value to the community." Sanger, however, retorted that the birth control movement was "urging smaller families …[and] offers an instrument of liberation to overburdened humanity" (Sanger quoted in Popenoe 1926, 149)

Mary Ware Dennett established the National Birth Control League to repeal the Comstock law in 1915. She advocated a "clean repeal" of the law rather than a "doctors only" bill advocated by Sanger that would give exclusive rights to physicians to disseminate birth control. (Dennett, 1926, 94-96,219-220) The hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church was opposed to any attempts to change the laws and put pressure on politicians to maintain the law, even for physicians. When Dennett's initial efforts for repeal failed, she stepped down as a birth control leader. After her sex education pamphlet, The Sex Side of Life, was banned Dennett continued to campaign for repeal of the repressive statutes. In 1930, the courts finally overthrew the ban on mailing sex education material due to her efforts (Chesler 1992, 143-145; Chen 1996).

By the late-1920s, birth control became more acceptable to physicians. In 1925, psychiatrist Adolf Meyer published a book based upon the 1923 birth control conference organized by Sanger. It was a "symposium dealing with the subject from a number of angles." His contributors included notable academics and university presidents who supported both birth control and eugenics.

By the mid-1930s birth control leagues had emerged in many states and in 1942 they united to become the Planned Parenthood Federation of America. In 1936, after the Comstock laws were overturned, birth control devices could also be sent through the mail. However, many states continued to outlaw birth control clinics until the late 1960s (Chesler 1992, 372-373).

Although few statistics are available as to the effect of the birth control movement during the early twentieth century, a dramatic decrease in crude birth rate from 1910 to 1940 occurred resulting in smaller families. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) and Department of Public Health, Education and Welfare (DHEW) imply this was due to many factors including increased use of contraception, decreased infant mortality rate, urbanization, increase in age of marriage, increased education, and the economic Depression. Other contributing factors included the beginning of the manufacturing of diaphragms in 1925, endorsement of birth control in 1927 by the AMA, and family planning included as a part of public health in the late 1930s (CDC 1999; DHEW 1977). In 1940, a study of 3,500 women and their contraceptive use, focusing on upper middle-class women, was published; subjects were interviewed in 1933. The study showed that 83% used some type of fertility control, including 77% of Catholic women. The authors, however, remarked that the "[declining] birth rate and the effectiveness of … particular contraceptive practices is not clear." (Riley and White 1940, p. 890).

Birth control and eugenics were linked. By the early 1920s, Sanger, like most health and social welfare professionals of the time, accepted eugenics. Sanger contended "an American race, containing the best of all racial elements could give to the world a vision and a leadership beyond our present imagination" (1921, 46). However, this would not happen until immigrants were no longer "herded into slums to become diseased, to become social burdens…We have huddled them together like rabbits to multiply their numbers and their misery"…. Out of these conditions come "the feeble minded and other defectives." (1921, 37, 40)

Some eugenic advocates promoted birth control as a eugenic measure including Edward A. Ross and Harvard geneticist Edward M. East. Robinson (1922, 16) suggested "there is no other single measure that would so positively, so immediately contribute towards the happiness and progress of the human race" than "knowledge of the proper measures for prevention of conception." Wiggam asserted that "when birth control is not universal it acts to decrease intelligence and character and increase incompetents and poverty" (Inman 1930, 17).

Other eugenic advocates were ambivalent about birth control. Economist Irving Fisher feared "race suicide of scientific and educated men and of well-to-do classes …But it is plain that the extension of birth-control to all classes will tend to rectify this situation" (1921, 224-225).

DeVilbiss (1923, 175) cautions "there is one great danger in the too wide acceptance of the practice of Birth Control…it might result in a sudden lowering of the birth rate… principally among the socially fit." Popenoe and Johnson (1918, 269) noted, however, that native born old- stock "women no longer bear as many children, because they don't want to."

A few religious groups were against birth control. The Catholic Church was against both birth control and eugenic sterilization. Charles P. Bruehl (1928), writing from a Catholic perspective, in Birth Control and Eugenics details the objections to these practices on moral and religious grounds. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints ("Mormons") was also opposed to birth control on religious grounds but considered it acceptable for certain medical or "inherited" conditions (Bush 1976, 20-22; Bush 1992, 168).

Although birth control was unacceptable to some eugenic and nativist enthusiasts, eugenic sterilization was championed by most. Physician Harry Sharp, who worked in an Indiana State Reformatory, began eugenic sterilizations surgery in 1899. He convinced the Indiana state legislature that sterilization of criminals, feeble minded, and others thought unfit would be a tax- saving measure. The first eugenic sterilization law was passed in Indiana in 1907. Between 1907 and 1931, 36 states enacted these laws (Laughlin, 1922, 1-4; Engs, 2005, 55). Laughlin developed a model sterilization law in 1922.

The eugenic sterilization aspect of the eugenics movement peaked with the United States Supreme Court decision, Buck v. Bell (1927), which upheld a states right to legally sterilize individuals considered "mentally defective." Many of these individuals were immigrants. Gosney and Popenoe (1929, ix) in Sterilization for Human Betterment discussed the results of 60,000 sterilizations in California, the highest of any state. They lauded the Buck v. Bell decision. Although some states repealed these laws, it was not until the 1970s that eugenic sterilizations went out of favor. In May 2002, the governor of Virginia apologized to all those who had been forcibly sterilized in his state as did Vermont, Oregon, North and South Carolina, and California between 2002-2003 and Indiana in 2006 (Klein 2002, Stern 2005). Information on voluntary sterilization to control fertility by the middle-class in the 1920s and 30s is not available.

Changes in the interpretation of the eugenics, immigration restriction, and birth control movements appear to come in about two decade intervals. The rest of the chapter will examine the evolving historiographies beginning in the 1950s when academics first began to research these issues.